Analysis: Russian Armored Vehicle Fleet, 2022–2025

A production level geared for endurance

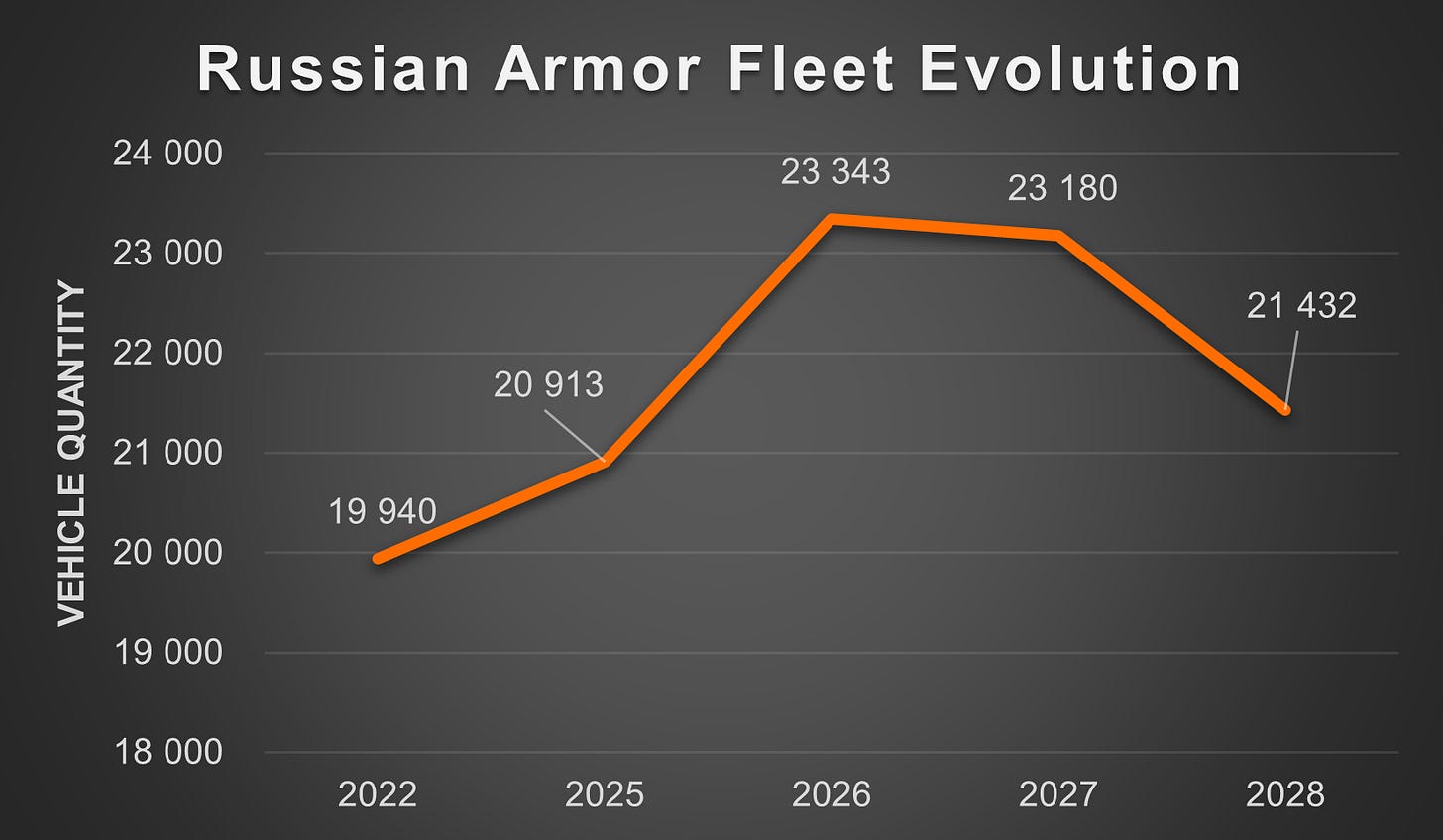

Current data suggests that Russia’s armored vehicle fleet is larger today than at the onset of the war in 2022. Contrary to recurring claims that Russia is running out of armored vehicles and therefore relying on infantry-led infiltration assaults, my analysis indicates that the fleet has actually grown by approximately 5% by the end of 2025.

Drawing on an assessment of losses, reactivation rates, and new production, supported by Jompy @Jonpy99’s OSINT work on Russian open-air storage sites and additional sources listed in my final post, I developed a projection model similar to the one used previously for Ukraine.

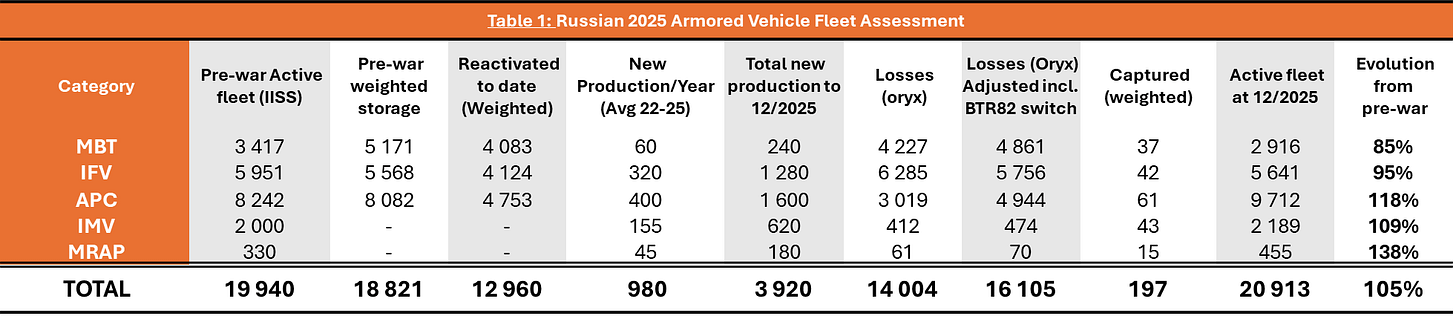

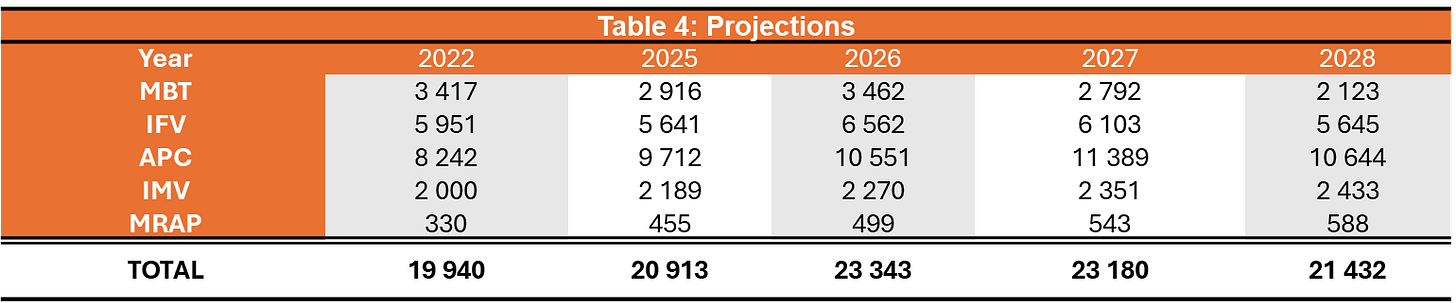

According to the simulation (see Table 1), the 2025 fleet shows:

MBTs and IFVs: slight decline relative to pre-war volumes

APCs: sharp increase of 38%

Overall total: from a pre-war inventory of 19,900 vehicles to roughly 20,900 in 2025

Looking ahead, and assuming conservative production and reactivation levels in 2026, the fleet is projected to peak around 23,000 vehicles before gradually declining as Soviet-era storage stocks are depleted. Even so, the model suggests that totals should not fall below pre-war levels before 2030. By that time, refurbishment capacity will likely shift to additional new production, not matching today’s total output but sufficient to offset current loss rates. A second scenario, of course, is that the war ends and new production is redirected toward replenishing the most modern classes of equipment.

1. Loss Estimates Adjusted by +15%

While the Oryx database remains comprehensive, a 15% upward adjustment is applied to account for unrecorded losses. Damaged vehicles are included to capture non-combat attrition: accidents, breakdowns, and so on.

Compared with Ukraine, for which I used a +25% factor, Russia’s superior recovery infrastructure and sustained territorial advances over two years enable more efficient towing and repair of damaged vehicles, justifying a lower adjustment. Newer “turtle tank” configurations also appear more resilient after immobilization, resulting in fewer total write-offs.

For projections beyond 2025, an average annual loss figure of 2,676 vehicles is used.

Note: For consistency, BTR-82s are classified as APCs, not IFVs as in Oryx.

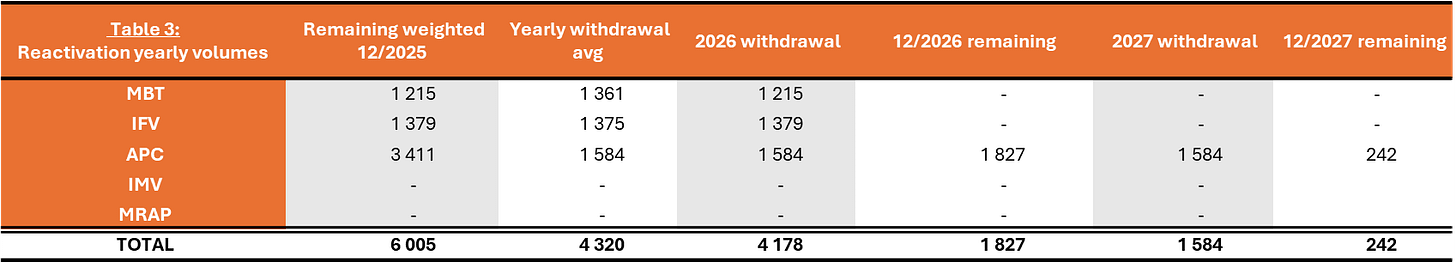

2. Reactivation Phase Expected to End by 2027

Russia entered the war with roughly 26,000 vehicles in storage, of which 16,000 have since been pulled from depots (visible via satellite). For this model, all are assumed to have been reactivated, without assessing for ongoing refurbishment timelines.

To incorporate cannibalization rates, critical given the variable condition of stored materiel, I applied the following weighting:

Decent (1:1): one stored vehicle yields one operational vehicle

Poor (2:1): two stored vehicles required for one operational vehicle

Worse (3:1): three stored vehicles required for one operational vehicle

This yields an effective, weighted storage pool of 18,800 vehicles, leaving 5,800 vehicles available for reactivation (weighted) as of December 2025.

At current refurbishment throughput, only marginal, non-viable hulls will remain by 2027, ending the reactivation phase. From that point onward, new production alone will cover losses.

For Ukraine, I had applied “worse” cannibalization assumptions across all stored vehicles due to extensive aging, poor storage conditions, and limited access to spare parts.

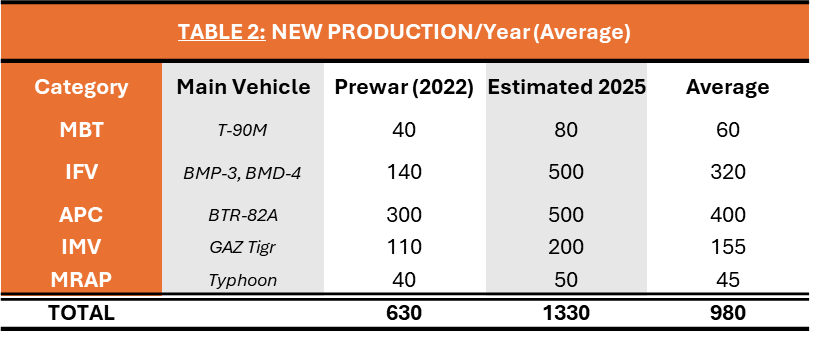

3. New Production Has Doubled Since 2022

This remains the most uncertain variable, as publicly available OSINT data is limited. However, based on industry reports, expert discussions, financial statements, and workforce changes, I estimate:

Annual production has doubled since pre-war levels, reaching approximately 1,330 vehicles per year across all categories.

For MBTs, I previously detailed that 80 units/year is a likely minimum, consistent with multiple independent assessments (see attached CIT study).

The most significant growth is in the IFV sector:

Pre-war production at Kurganmashzavod: ~70 vehicles/year (for both BMP-3 and BMD-4)

Late 2010s peak: 150+ vehicles/year

Current output after four years of war: likely 200+ vehicles/year, consistent with factory statements claiming a tripling of peacetime output

Storage stocks contain only a few dozen BMP-3 hulls, suggesting current IFV totals reflect primarily new production. KMZ’s financial and staffing expansion (almost doubling workforce) supports growth to the current level, while making significantly higher output unlikely at present. Further monitoring is required for future updates.

4. Captured Equipment Remains Marginal

Captured equipment plays a negligible role in total force structure.

A 1:4 ratio is used to estimate the portion of captured vehicles reintroduced into Russian service. While Russia can refurbish Soviet-era equipment more easily than Ukraine, many foreign systems can only serve as trophies.

5. Projections: Russia Is Not Exhausting Its Armored Reserves

Modeling forward with constant 2025 loss levels and stable new production, the total fleet remains above 2022 levels through at least 2030.

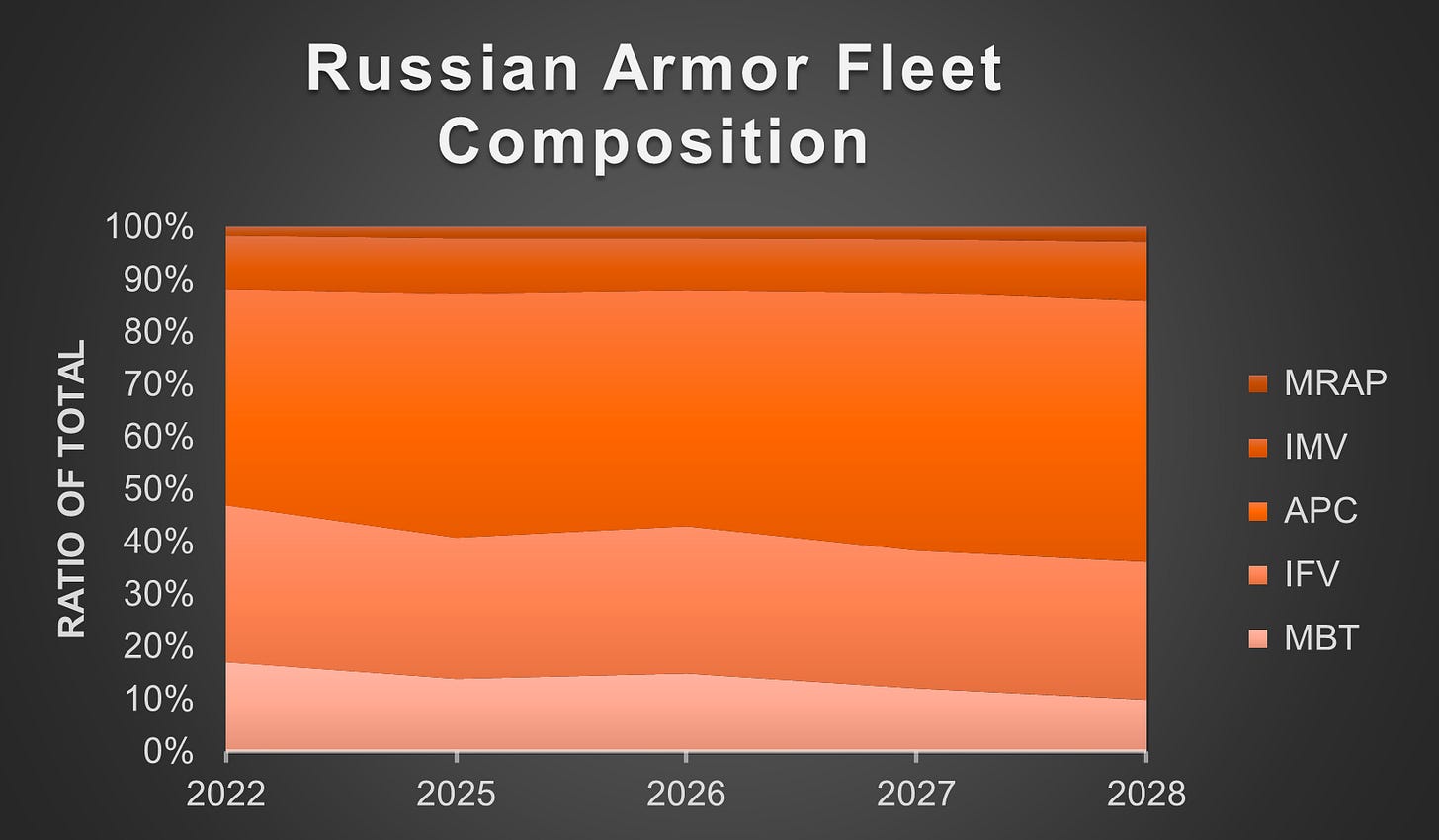

However, the internal composition shifts:

MBT and IFV shares decline in both proportion and absolute numbers, though not to critical levels.

APCs and other support categories remain abundant.

Even with changes to assumptions (lower production, higher losses, lower 2022 active fleet or harsher cannibalization) the core conclusion holds: Russia maintains a fleet at least comparable to pre-war strength, roughly 19,000+ vehicles. They have reactivated an incredible quantity of vehicles, enough to offset losses suffered so far.

Meanwhile, armored assaults remain a consistent tactic, with monthly losses in the low hundreds during such operations. These vehicles remain essential for assaulting fortified positions, though increasingly paired with light motorbike units and infiltration-oriented assault teams.

Recent imagery from Russian rear areas shows growing reserves and training formations, suggesting the formation of strategic armored reserves. Their intended purpose remains open to interpretation: potential future operations in Ukraine, regional deterrence, or both.

As for the reason why armored formations have reduced frontline visibility, several explanations exist. My view is that current availability meets present tactical requirements in a drone-dominated environment, while manpower constraints also limit the deployment of large armored formations and supporting infantry units together.

Sources (selected):

https://armstrade.org/includes/periodics/news/2023/0904/094575075/detail.shtml

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03071847.2024.2392990#d1e101

Thank you for this. Very useful info. Found you through Jompy on Twitter.

BTR’s aren’t seen all that often compared to BMP’s of various vintages. Not sure why they dominate the graph. Western nomenclature IFV/APC is in my opinion not really helpful, the key distinction is whether it has tracks, or it is wheel+amphib. (as a footnote, BMD’s straddle the two categories, but are fallen by the wayside due to lighter armor vs drones). Would be useful to quantify the contemporary 72’s and 80’s upgrade builds, which remain backbone of the RF tank force. Likewise the tank chassis derivative vehicles like TOS, BREM, SPG’s, SAM’s, and bridge-layers, which together may well outnumber the tank itself in current production- esp for the T90 chassis. Lastly, Oryx is a far from reliable source, it has led too many observers astray.